For the 2019 edition of the 1-54 Courtyard Sculpture Commission, Kiluanji Kia Henda has been selected for his evocative work, The Fortress

NewAfrican published an interview with Kiluanji Kia Henda on their October issue, on the occasion of his monumental sculpture commission at 1-54 London 2019. As part of our media partnership with NewAfrican, we’re sharing it here.

After the modernist artist Ibrahim El Salahi, selected for the sculpture commission in 2018, this year is the turn of the Angolan artist, Kiluanji Kia Henda, who will unveil his monumental sculpture The Fortress on the ground of the Edmond J. Safra Fountain Court at Somerset House during the next edition of 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair. The commission, supported for the second year by the Kamel Lazaar Foundation (KLF), allows artists from the African continent to produce and exhibit a large-scale sculpture in the majestic backdrop of Somerset House.

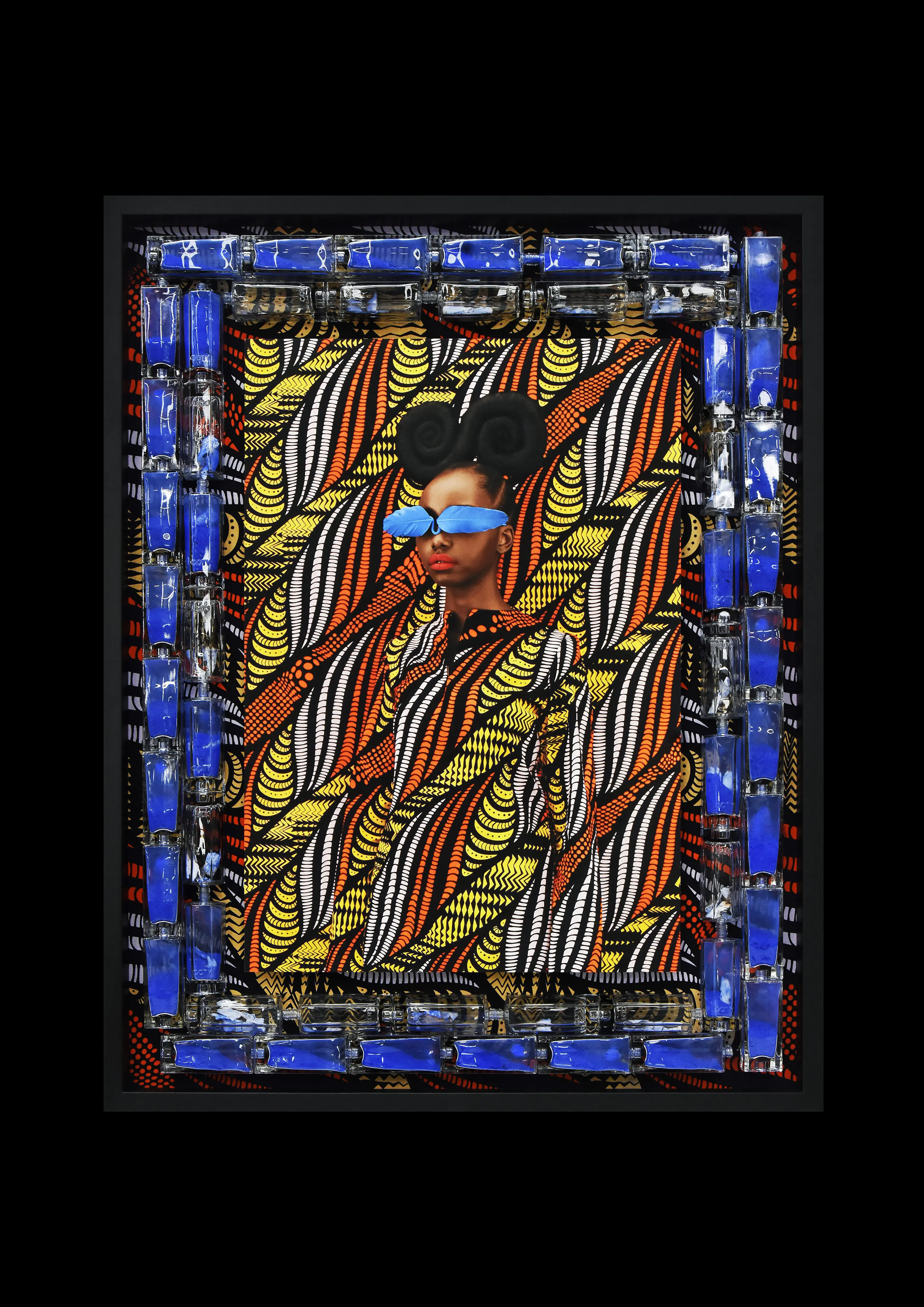

Part of the series in progress A City Called Mirage, The Fortress stands as a reminder of the ephemeral nature of human constructions. The series was originally inspired by processes of erosion and transience the artist witnessed in the Angolan desert, culminating in an imaginary cityscape in which he investigates the contemporary global urbanisation oscillating between virtuality and desertification. Kia Henda uses science, mythological fiction and irony as ways to transcend the pessimism of hyper-criticism and the aesthetics of the ruin, often deliberately creating new elements to interpret society. Humour and irony are essential elements of his own vision and practice that attempts to investigate notions of identity, politics, and the perception of post-colonialism and modernism in Africa. Working in pervert complicity with the historical legacy, Kia Henda sees the process of appropriation and manipulation of the public spaces and structures, and the different representations that makes part of the collective memory, as a relevant complexion of his aesthetical construction.

As a self-taught artist, grown up in a household of photography enthusiasts actively engaged in politics, Henda could not be part but of that generation of young Angolan artists living and working in a country that suffered a long-term civil war and who are able to perfectly combine art and commitment, poetry and militancy, lightness and solemnity.

Henda lives and works between Luanda, Angola and Lisbon, Portugal. He is represented by Goodman Gallery, the pre-eminent art gallery on the African continent, whose role has been pivotal in shaping contemporary South African art, bringing David Goldblatt, William Kentridge, David Koloane, Sam Nhlengethwa and Sue Williamson to the world’s attention for the first time during the apartheid era. They will open a new space in London in October 2019.

Can you tell us more about how was the original series, “The City Called Mirage”, born and what The Fortress means to you?

KKH: The project “A City Called Mirage” was conceived at a time when the city of Luanda was experiencing a boom in construction. It was important to consider how that building symbolised the great social exclusion. People looked at these new impressive buildings appearing in the city as a symbol of development, but the truth is that the vast majority would never have the opportunity to enter such spaces. Architecture has always been a passion and the desert has always been a cause of great fascination. I’ve visited several times the Namib Desert in southern Angola, which got me thinking about the parallel that exists between the emptiness of cities that arose in many parts of the world, which do not house a single inhabitant, and the emptiness of the desert. If we add the millions of square meters of buildings that are vacant at the moment, we would be in the presence of a huge concrete desert, a desert caused by the perverse capitalist speculation of a vital asset as housing.

From the Jordan desert to a volcano crater in South of Italy, up to an historical building (Somerset House) in central London. Have you ever thought your sculpture would end in such a different frame than the one you created initially?

KKH: No, never before I had anticipated that the sculpture could move elsewhere on the planet. This sculpture was designed for the desert, but with the intention to address a problem that is global. In the case of London, it was inevitable to think of a Europe that has gradually converted into a fortress with the growth of the extreme right. The current crisis of African immigrants is very symptomatic of this frustrated looking for a getaway that we can call home: a mirage caused by the dreams and desires that often never materialise, or even end in tragedy.

Architecture, public space and social identity seem to be questions you often explore within your practice. What makes it interesting for you to exhibit at 1-54?

KKH: I have followed how the work at 1-54 is held around African contemporary art and have called into question the ability of fairs in general as legitimate artistic creations of space. What cannot be questioned is their ability to promote a certain visibility for artists. In this case what can develop a special project for the fair in an unconventional space, making this a unique opportunity for my career. The work will have sufficient independence however, so people can reflect on issues related to the work beyond the commercial aspect which is the main purpose of a fair.

In your latest interview with Tate, you said “You have to apply humour if you want people’s attraction, humour is a way to put your finger on the wound, it’s a delicate way to deal with traumatic experiences.” By applying irony to your practice, your work Despite raising critical questions about the national consciousness and / re-constructing history and still feel light-hearted look. How do you manage to Obtain that?

KKH: It is hard to live in a country [Angola] that so far does not have the courage to confront its own history. We live in different cycles of violence from slavery to civil war. It is necessary to look at these cycles of violence as they still disturb the peace of many people, preventing the possibility of gaining a true social peace. There is a great reluctance to talk about the story because many of his protagonists are still alive, and some with immense political power. It is necessary to find strategies so that reflection on the past is made without fear and paranoia of persecution. History is a bitch. It is not easy to maintain an affectionate relationship that is healthy and without sorrow, but we cannot survive without it. Maybe it will be easier to take things in a lighter way, but aware of our commitment to free the minds of trauma and remorse.

Some curators described your work as “the flight line towards the future to be invented, more than expected.” The conceptual artist always on the move, can you tell us more about one of your next projects?

KKH: I was invited by curator Luigi Fassi to carry out a project for the MAN Museum in Nuoro, Sardinia, where I discovered a paradise, a heavenly landscape. But there is no concept of paradise without there also being a hell. It is amazing how this small territory was so forcefully the western culture of war, especially in the twentieth century with the presence of numerous military bases. The project is also related to the crisis in the Mediterranean – the human need to emigrate, which is an important chapter in the recent history of Italy during the twentieth century with thousands of people fleeing from hunger, even to destinations such as North Africa. We must speak to that, because today there is an insensitivity in dealing with African migrants fleeing governments that instill a collective amnesia.