Kapwani Kiwanga was born in Hamilton Ontario. Initially studying anthropology and comparative religion at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, and art at Le Fresnoy: Studio national des arts contemporains in Tourcoing, France, she currently lives and works in Paris. In this interview Kiwanga discusses with Mukami Kuria the role of the archive in her practice. A shorter version of this article has been published in the October issue of NewAfrican.

You were trained as an anthropologist, so how did you begin as an artist – that is if you consider yourself an artist?

I find artist such a weighty term, it means a lot for different people. I ‘d rather think of it as: I have ideas, I would like to share them and try to propose new things. I guess that’s how I try define it, without defining it.

Was it an inevitable transition, translating your research into artistic practice?

It wasn’t so inevitable. I thought I was destined to be an academic, but I quickly realised that that was not going to be the right environment for how I wanted to transmit ideas. I started with documentary film after finishing my degree. However documentary film also was a bit too formatted for me. I was searching for more free forms, which I could use to express and share ideas and concepts.

Does your practice then incorporate different media to widen the language in which you express your ideas and allow you to revisit history through multiple lenses?

It depends on each of the projects, each of the concepts I’m looking at. The medium comes from the investigation. So I don’t have a fixed medium, it varies. Sometimes the material itself holds it’s own importance or its own documental or archival status. For example the Castor Oil plants in Kinjiketile Suite, or any other material itself can be a document, not a written article or a newspaper clipping. Using something which comes from a particular place or time or may have been somehow, instrumental, is also one way that I explore. That material itself becomes the research terrain.

There is also an interest in trying to make two different cultural systems or cultural expressions meet or to join them somehow, in order to see what new forms emerge. That’s also part of my desire for things that have been sequestered dialogue with one another.

One work that I’ll be showing at 1:54 is called Ifa Organ. And that’s mixing Eastern European, Central European musical instrumentation and notation and the Ifa divination system from West Africa and the diaspora. I think that’s another way this question of media comes about.

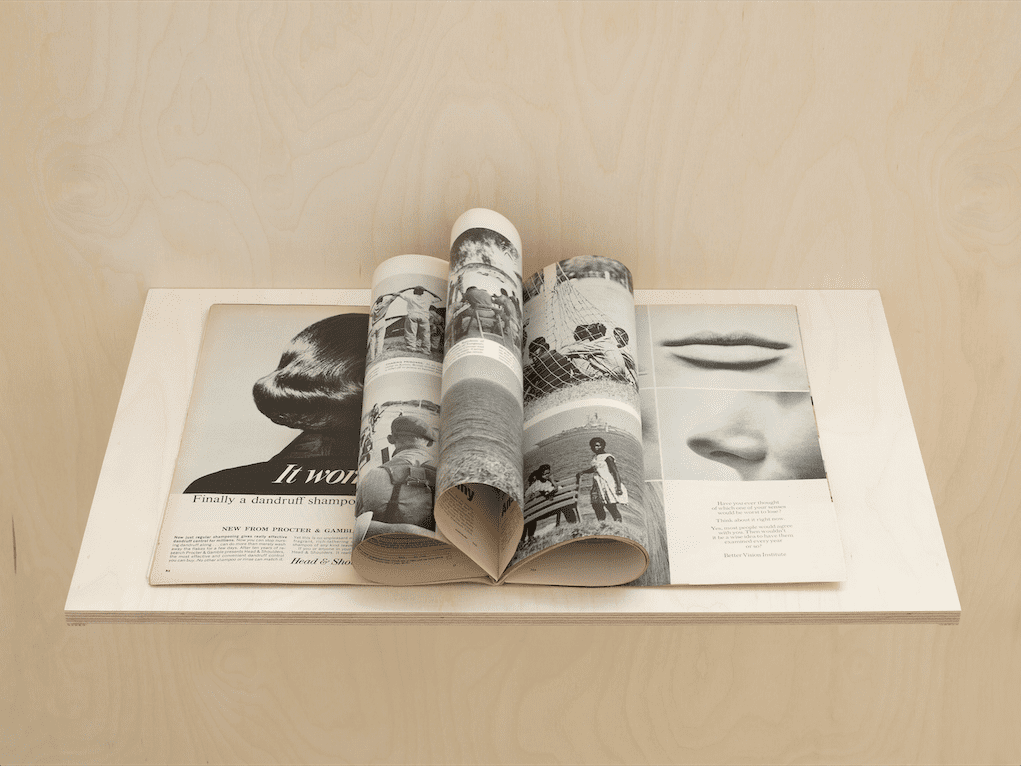

This year at 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, you will be exhibiting a really special project, Flowers for Africa. 1:54 is not the first time you’ll be showing in London, earlier this year you had a solo show Kinjiketile Suite at South London Gallery and Mythopoeia at Tiwani Contemporary. With these three shows and more generally, the archive is a constant feature in your work. How did this interest come about? Is it both a personal and larger political history that infuses your practice with the invocation of the archive?

There’s a desire to understand the past. So yes there’s a political and social interest, as well as an interest in marginal histories. Although Flowers for Africa is less of a look at a marginal history, there’s nonetheless an interest in the fact that these flower arrangements are not the centrepiece of what’s happening. The flower arrangements are décor in the background, peripheral somehow; although they are important in creating the atmosphere of officiality when passing over power. I’m also interested in those things that may have fallen through the cracks; everyday experiences of larger events, the invisible, the unseen, to shift the way one looks.

I think these floral arrangements points to that, but sometimes in my other work with large installations such as Kinjiketile Suite, I use installations to make one aware of the scale of the history’s authoritative stance and narrative. One’s body in relation to the scale of the installations often makes one feel small or enables them to anchor themselves in their experience. So I ask people to listen, walk, meander, to look closer, to bend down.

So one way I work is through the huge installations or trying to blow up and make larger these systems, which are quite organising or authoritative. Another way is asking people to think about the invisible, the unseen. So the installations shift the way in which one looks. The archive is interesting as it extends to the temporal reflection as well. As you are looking at these bouquets, you know that the bouquets are going to fade away depending on the duration of the exhibition – sometimes they are displayed for two months, and they do progressively; if you come periodically, you see the progression. But there’s already this sense of a vanity.

With your Flowers for Africa project, is there a sense of continuity in your work, using plants to signify important times in Tanzanian and African history conceptually?

The continuity is inverse in that I started with Flowers for Africa in Dakar in 2013 so that came first. There’s an interest in documents definitely as well as questonning whether flowers, plants or organic material can also act as a document of some sort. What kind of knowledge or insight could they offer? The idea of witnesses (even silent) is key for me.

Even if its not a witness its also the nature of the material, what of its hardness, its softness, its colour? What could that also give us in terms of information? It’s looking at different knowledge systems, and different ways of understanding. A part of my work is interested in questioning archiving and documenting. There’s also the construction of the academic or the scientific voice which intrigues me. I try to take apart scientific language and looked at it closely. There’s also the more supernatural as well as more organic and geological perspectives.

Another solo show I’ll be presenting in October at my Parisian Gallery (Galerie Jérôme Poggi) is another project altogether; I’m focusing more on geology as a prehistoric record. What did we have before written documents and before we existed as human beings, before our cultural systems came to categorise, explain and narrate? It’s these ideas of different entrances through different materials: the rock, the earth, the plant, flowers.

In Kinjiketile Suite it was important, this notion of nurturing and caring for, cultivating. It’s the same with these political or ideological concepts, they need to be cared for. What happens in the Flowers for Africa project, it’s more of a reactivation, a question of maintenance, more than an act of care.

Resuscitating a moment to revisit so one can look at it again. And through looking at this moment again what to do we understand? When looking does it simply remind us or do we see something differently? These moments are reactivated fully knowing that you cannot go back to that time; that time has passed. We can look back and ask “what would have happened if we had embarked on another direction?”. It’s revisiting that point to reflect and to look, just to have more perspective.

Somehow I think I also try to care for that moment of hope and enthusiasm, which I think is important. Although sometimes these moments failed, sometimes more than others and every situation and every period is a different kind of fulfilment or failure of this moment that I pull out in Flowers for Africa. For me it’s also this idea of a retro-motivator or a retro-motor somehow. You go back to then move forward. These questions of temporality, it’s very non-linear and it develops, it goes back and forth, it folds over, it’s never something which is going towards a telos. Because in the way I see things there is no telos, there is no universal end point.

You’ve spoken to how it is that your practice negotiates time and temporality.

Similarly on notions of time and storytelling would you consider that Flowers for Africa is largely about you telling not your story but a story that is important to a number of people?

It is, but it’s also a story that is general and silent. It’s non-official discourse, it’s not the photos or newsreel sources on which these flower arrangements are based on that have in most cases men shaking hands or signing papers. I’m not interested in representing them or disseminating their discourse, which presented their hopes and aspirations and which spoke to what a nation is meant to embody. It’s more about that charged moment of gaining sovereignty, which has slipped away. Also I wonder who were these witnesses on the sidelines who were not framed in the photo. It’s thus, also a question of the everyday experience of these important historical moments and the micro-stories.

I’m intrigued by the idea of flowers bearing witness, and the questions of the staging of power and the performance of power. Flowers for Africa is very specific to the period of independence across Africa, and the departing colonial powers. Do you then think it’s occupied with questions of ownership?

Ownership is not a word that really resonates for me, it is too exclusive, I opt of inclusion. All of the photos and newsreels I’ve used to date for Flowers for Africa have come from national or public archives. I’ve avoided using private collections. It was important that these images were accessible theoretically to all. I am aware, of course, of various real barriers to such accessibility but the question of archives and documents being available to everyone is important for me. Ownership for me is a funny word, I feel closer to the ideas of things being collectively owned, things that are shared.

Does the question of ownership then map on to other questions that Flowers for Africa raises, such as the politics of the horticultural industry, and the relationships past and present that continue to define it?

It’s definitely a part of it somehow. It wasn’t the main issue when I started the project. Of course it became very evident, even with questions of temporality, its also mapping economic and political power now. I started this project in Dakar when I was on residency and I went to find florists that might want to participate. I was trying to get a sense of where I would get the flowers I needed. There is a flower market where some flowers are locally cultivated in greenhouses, which seem to have been around for generations. Speaking to one of the older florists, she told me that their business was started from needing to cultivate a small garden to cater to their clients who were mostly Europeans, and were there in the Colonial era and just after. That grew and grew and of course the Senegalese needed to create a greenhouse in order to cultivate some of the flowers that they sell on.

It’s also this interest of what I touched on before; these cultural meetings. It was started locally by Senegalese. They started this business to cater for particular cultural tastes and now it has become part of a very particular part of their economy, local economy – though I wouldn’t say it has been democratised amongst all the families or regions of Dakar.

There is the international phenomenon of mono-cultivation. Of course, in the case of flowers for export, other crops are not grown in their place. It therefore also looks at where these flowers come from. Through speaking with different florists, who would look at the year as well and the month in which these events take place, we would then try to figure out whether the flowers would have been Senegalese or would the flowers have been flown in? Looking at photos from the time – photos with either the Queen, the Duchess of Kent or the Duke of Edinburgh – the photos don’t contain any information documents which would confirm that. It would not be unthinkable to imagine that some flowers could have been flown in. I do not know that for sure, but it definitely does evoke those questions.

Relating to the Flowers For Africa project and your artistic practice, do you feel that there is a weight that comes with attempting to pay homage to African independence movements? Similarly do you think that there is a weight affixed to labelling artists as “African artists”, or does it all come together in a whole identity of “being African” or pan-Africanism, which simultaneously has its nuances and differences?

I don’t feel the weight of representing independence movements. I try to be as transparent as I can in my position. It doesn’t try to be either authoritative or exhaustive, it’s really an interpretive stance which I assume.

I also try to be honest with my research and the whole process of finding a document, looking at that document and interpreting it. There’s a human aspect to it, which I try to be honest about, that it could be flawed in its interpretation as well. That is important for me in my work, in negotiating reproduction. Something is reproduced conceptually and each time it is reproduced once it’s faded away. If somebody would like to continue reactivating the flower arrangements, different people will interpret them at different times and there’ll be slight differences. I therefore don’t see my work as a reproduction, but as an interpretation.

The weight you speak of, I don’t feel it, because I don’t at any point think my work is exhaustive, authoritative or is a reference per se. It is a political gesture in some way, one that is very personal. It is also about all these micro-gestures, so it’s not one which I can vindicate as an activist gesture or that I pretend it to be. I think it would be quite pretentious to think it so. But you have to be a bit more lucid in one’s position.

What I’m trying to do is to acquaint myself with these various historic times, and questions, and more generally an interest I have in power dynamics. With this project I have chosen to look from the African continent at these global questions of power dynamics. This project is a way for me to acquaint myself with different archives, consulting documents and simply pondering on those moments. In this process, this was the most natural gesture which emerged.

In terms of the “the African artist”, it’s something I’m not too concerned with. I am quite sceptical of most labels for the simple fact that they simplify. There are labels some people want to grab onto; perhaps other people find it important to re-vindicate the label. The important thing is who is labelling who and to what end? If one speaks for themselves they affirm an identity, but if this naming comes from elsewhere it should be questioned.